Image of Grey Cliffs from 1930. Note the extensive sagebrush, with pinon pine and juniper trees moving in. NPS.

This article is part of a series of posts showcasing articles published in the Winter 2022 issue of “The Midden”, Great Basin National Park’s semiannual resource management newsletter. This is the third installment of this series, which introduces readers to some of the issues, projects, and management strategies currently occurring in Great Basin National Park. Our series does not feature every article published in “The Midden”, so the best way to stay fully up to date is to check out this winter’s issue!

In this article, Bryan Hamilton, the Park's Integrated Resource Program Manager, explains shifting baseline syndrome through the example of sagebrush in Great Basin National Park.

Shifting Baselines

By Bryan Hamilton, Integrated Resource Program Manager

Wait!! What? This wasn’t always a forest?

It is easy to see national parks as static and unchanging. But the world is always moving, and slower, gradual changes often go unnoticed. Over time these changes may become accepted as the status quo, the way things have always been. This phenomenon is called shifting baseline syndrome (Soga and Gaston, 2018).

Shifting baseline describes a gradual change in our accepted norms and expectations for the environment across generations. Our tolerance for environmental degradation increases and our expectations for the natural world are lowered. For example, bison are absent from 98% of their historic range. Yet the functional extinction of bison is often viewed as a conservation success story. Five billion passenger pigeons once darkened skies in eastern North America. It’s impossible for anyone living today to grasp the spectacle and ecological impact of those now extinct flocks. While these examples may seem cliché, distant and even overly dramatic, they show how shifting baselines affect our perception and acceptance of the state of the natural world. In truth similar changes are occurring all around us.

One example is in the vast sagebrush ocean of the Great Basin.

More than any other species, sagebrush defines the Great Basin, forming one of the largest intact habitats in the country. Many animals, like sage grouse and pygmy rabbits, are only found in sagebrush. Sagebrush is also important for recreation and agriculture, carpeting beautiful open spaces with lush springtime wildflowers, vast vistas, and deeply dark night skies. But sagebrush is also one of the most threatened ecosystems in North America.

Fire in the Great Basin is as natural as wind, sun, and rain. Ecosystems here evolved under frequent and low severity fires (Chambers, 2008). Sometimes called “good” fires, many were ignited by lightning, others intentionally started by Native Americans, who used fire as a tool to manage their environment. But colonization virtually eliminated fire as a natural process from the Great Basin, when aggressive fire exclusion began in the 1920’s. This policy had a slow but dramatic effect on sagebrush plant communities.

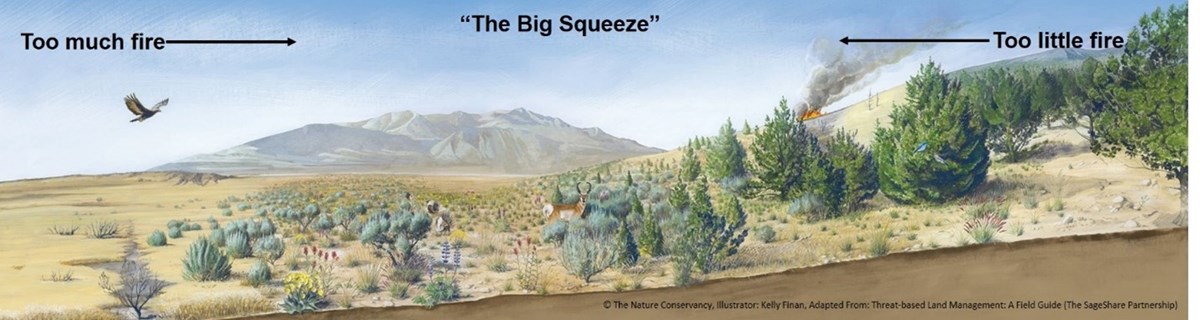

Without fire, conifers like pinon pine and juniper outcompete and overtake sagebrush. Singleleaf pinon pine and Utah juniper seeds are carried into sagebrush habitat by birds or small mammals, where they establish under a “nurse plant.” Nurse plants provide a cool, moist microclimate, with fertile soil for young trees. Over time these trees “overtop” their sagebrush host, out competing it for critical resources of light and water. Fires historically reset this process every 25-100 years (Knick et al., 2005). In the era of fire exclusion, pinyon juniper woodlands have increased ten fold (Miller and Tausch, 2001), fragmenting the sagebrush ocean into lakes, ponds, and puddles (Welch, 2005).